HELEN by Euripides

- Friday, July 29Curium Ancient Theatre

- Saturday, July 30Curium Ancient Theatre

- Performances start at:21:00Please arrive at Curium Ancient Theatre before 20:00

- Duration:

110 minutes

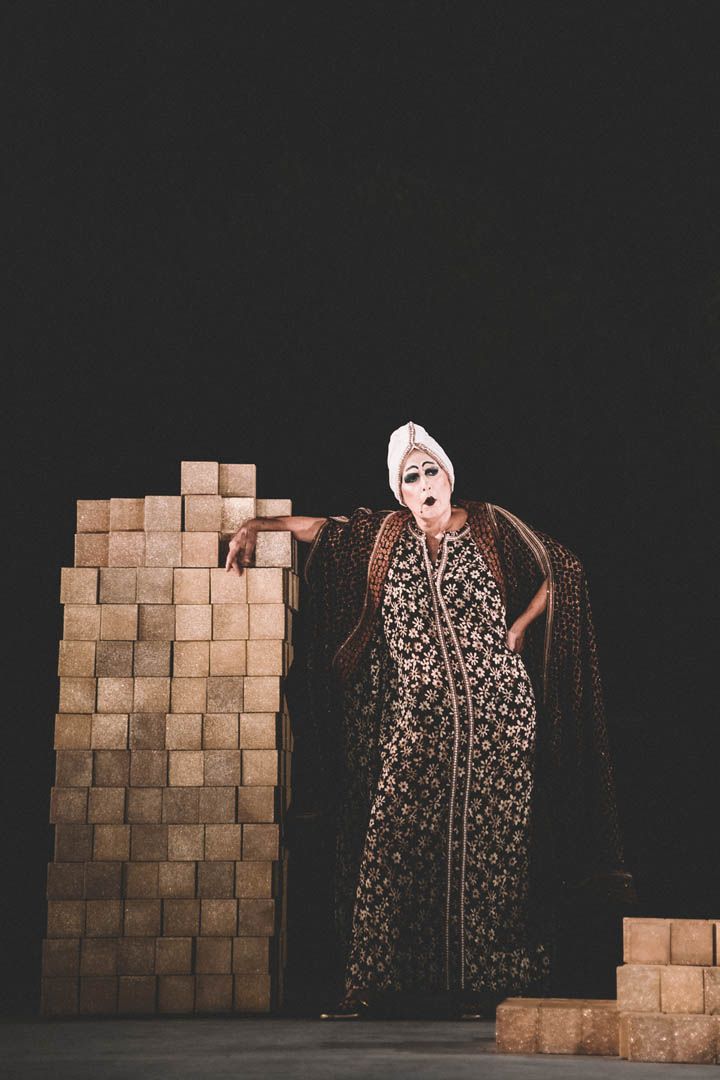

The National Theatre of Northern Greece (NTNG) returns to the Festival three years later and presents Helen by Euripides, translated by Pantelis Boukalas and directed by Vassilis Papavassiliou, featuring an ensemble of actors and musicians on stage.

Written in the aftermath of the Athenians’ crushing defeat in the Sicilian Expedition, Euripides’ Helen is noted both for its anti-war qualities and its focus on virtues such as the power of an oath and intelligence, both personified in the form of the titular heroine. Drawing on the version of the myth created by the lyric poet Stesichorus instead of Homer’s best-known version, Euripides portrays the Trojan War as a massacre committed for a phantom rather than a real woman.

Helen that is almost unduly classified as a “tragedy” is also characterized by its comic elements. NTNG’s production highlights these elements through an imaginative directional approach, creating a festive atmosphere, an anti-war conflict on stage.

WITH ENGLISH SURTITLES

- Translation:

Pantelis Boukalas

- Direction:

Vassilis Papavassiliou

- Associate director/Dramaturgy:

Nikoleta Filosoglou

- Set/Costume design:

Aggelos Mentis

- Music:

Aggelos Triantafyllou

- Choreography:

Dimitris Sotiriou

- Lighting design:

Lefteris Pavlopoulos

- Orchestration/Music coaching:

Yorgos Dousos

- Music coaching:

Chrysa Toumanidou

- Assistant to the director:

Anna-Maria Iakovou

- Assistant to the set/costume designer:

Elli Nalbandi

- Assistant to the choreographer:

Sofia Papanikandrou

- Production coordinator:

Athanasia Androni

- Stage manager:

Marina Chatziioannou

- Photographs:

Tasos Thomoglou

Cast:

- Helen:

Emily Koliandri

- Menelaus:

Themis Panou

- Theonoe:

Agoritsa Economou

- Theoclymenus:

Giorgos Kafkas

- Old woman:

Effie Stamouli

- First Messenger:

Dimitris Kolovos

- Second Messenger:

Angelos Bouras

- Teucer:

Dimitris Morfakidis

- Therapon:

Christos Mastrogiannidis

- The Dioscuri:

Nikolas Marangopoulos,

Orestes Paliadelis - Chorus:

Nefeli Anthopoulou,

Stavroula Arabatzoglou,

Natassa Daliaka,

Eleni Giannousi,

Elektra Goniadou ,

Sofia Kalemkeridou,

Aigli Katsiki,

Anna Kyriakidou,

Katerina Plexida,

Marianna Pourega,

Foteini Timotheou ,

Chrysa Toumanidou,

Loukia Vasileiou,

Momo Vlachou,

Chrysa Zafeiriadou - Musicians on stage:

Yorgos Dousos (flute, clarinet, saxophone, kaval),

Danis Koumartzis (double bass),

Thomas Kostoulas (percussion),

Pavlos Metsios (trumpet, electric guitar),

Haris Papathanasiou (violin),

Manolis Stamatiadis (piano, accordion)

DIRECTOR’S NOTE

“a mixed but legitimate genre”

Theoclymenus, king of Egypt, is with his tailor. It is the final fitting for his wedding suit. Or, if you prefer, he is on the steps in front of the church, like the hero of a Greek film from the 50s, waiting to welcome his bride, bouquet of flowers in hand. It’s just that the wedding isn’t going to happen. He’ll be jilted at the altar, because she has already set sail with a tail wind for home—for Greece, and more specifically for Sparta, since the bride is none other than Helen, the famous, the one and only Helen of Troy, daughter of Tyndareus and hatchling of Zeus and Leda. And the daughter of Homer, too, for it was he who wrapped her in the swaddling clothes of myth, the better to present her as the victim of Paris’ kidnapping and thus the cause of the Trojan War, a war which would unite the disparate elements of the Greek world against a common enemy for the first time; the war that would set its seal on the birth of the confrontation between Europe and Asia—for, as Paul Valéry put it so clearly, “Europe is a peninsula of Asia”.

The myth of Helen myth includes at least three kidnappings and five weddings. An innocent young girl is kidnapped by Theseus, symbolizing the betrothal of Athens and Sparta. Which makes it an entirely Greek affair. The second abduction, however, involves a “foreign element” who goes by the names of Paris and Alexander. It is Paris who takes her to Troy with everything that will ensue— the material, in other words, that Homer will develop in such detail in the Iliad. But we should not forget that something critical happened between Helen’s first and second abductions: her marriage to Menelaus which, following on as it does from the Theseus episode, had restored Peloponnesian unity. However, the myth remains duplicitous: descriptive on the one hand, interpretative on the other. Variants are the fate of myth. And thus, as time passed, a version began to take shape which was proposed two and more centuries after Homer by Stesichorus, Herodotus and Gorgias among others, and was then adopted by Euripides for his own Helen. According to this version, Helen never actually arrived at Troy. She was abducted, certainly, but not by mortal Paris, but rather, it was a god, Hermes himself, who took her, and Hera’s bidding—the goddess had her reasons. And Hermes did not take her to Asia Minor, but to Egypt, to the land of good king Proteas, who was a philhellene to boot. So she spent the ten years of the Trojan War in Egypt, and is still there seven years after its end, as her legal spouse, Menelaus, is lashed by stormy seas which confound his every effort to return home. In the end, he is washed up on an Egyptian shore with a few comrades. He has dragged a Helen along with them, but she’s not real, just an eidolon, a simulacrum of Helen, the phantom look-alike which Hera had deceitfully palmed off on Paris. But Proteas is no longer ruler of Egypt, having died and been succeeded by his son, Theoclymenus. And he, as is only natural given his red-blooded maleness, covets the real, exiled Helen. In fact, he’s madly in love with her. In contrast, the fake Helen, the one Menelaus has brought back with him as the spoils of war, has been burdened with all the curses and anathemas of Greeks and Trojans alike for the war and suffering she has caused. QED, the real Helen is innocent: she has no blood on her conscience.

In 412 BC, in Athens, Euripides presents her case in the “trial of Helen”. In the litigious “closed city” that is Athens in the aftermath of the destruction of the Athenian fleet off Sicily, the poet engages in a complex bit of demystification and entertainment based on the Sicilian orator and sophist Gorgias’s “In praise of Helen” which had made such an impression on the Athenians fifteen years earlier. And this in a climate of collapse that foretells the twilight of the golden age of Athenian democracy.

The comic poet Cratinus, a contemporary of Aristophanes and Euripides, once said that both men “had common interests”. He did so, one may surmise, to raise a laugh. But, in fact, both poets trespassed repeatedly on the other’s territory—they did it so often, in fact, that their trespass was immortalized with the gerund “Euripidaristophanizing”. Now let’s take a look at the facts. Helen was presented in 412 BC, and Aristophanes would write his colleague into the Thesmophoriazusae (or Women at the Thesmophoria) the very next year. In it, he has Euripides converse with none other than ‘Helen’ herself through a flurry of quotes.

So, is it a tragedy or a comedy? The question is important from a literary point of view. Still, the acts of the poets, which is to say their works, stand as proof that, as Emmanuel Roidis put it, comedy isn’t constantly and continuously comic, just as tragedy can be tragic by exception, making tragicomedy “a mixed but legitimate genre”, as Dionysios Solomos might have put it.

Vassilis Papavassiliou

NATIONAL THEATRE OF NORTHERN GREECE

The National Theatre of Northern Greece (NTNG) is currently the largest theatrical and cultural organisation in Greece. With 4 indoor stages, 2 open-air theatres, and Greek and international tours, the NTNG has been operating as an active cultural hub since 1961.

The new institutional framework of the NTNG was enacted in 1994. Pursuant to this, the theatre is run by a seven-member Board of Directors and an Artistic Director.

The NTNG is supervised and subsidised by the Ministry of Culture and Sports.

The NTNG has been a member of the Union of Theatres of Europe (www.ute-net.org) since May 1996 and served as a member of its Board of Directors until 2013. The NTNG is also a member of the International Theatre Institute.

The annual repertoire of the NTNG combines in-house productions, co-productions with other theatre organizations and special tributes. The NTNG also hosts Greek and international guest performances. Its activities expand well into other cultural domains, such as education, literature, fine arts, exhibitions, conferences and international festivals, educational theatre programmes and other social activities.

Based on the core belief that education and culture are basic necessities and wishing to remain a theatre open to society, the NTNG implements a strategy founded on the following:

- Wide-ranging repertoire.

- Low ticketing policy and various classifications of benefits.

- Corporate social responsibility that focuses on population groups who for various reasons have no access to theatre performances.

- Emphasis on the production of high-quality performances for children and young people.

- Awareness-raising social activities.

- Strengthening bonds and collaborations with cultural organisations, municipal authorities and charities.

- Reinforcing the theatre’s international presence.